This research published in 2024 was supported by the Heising-Simons Foundation. The original research published in 2002 was supported by the Foundation for Child Development and the Center for Labor Research and Education at the University of California at Berkeley.

Preface

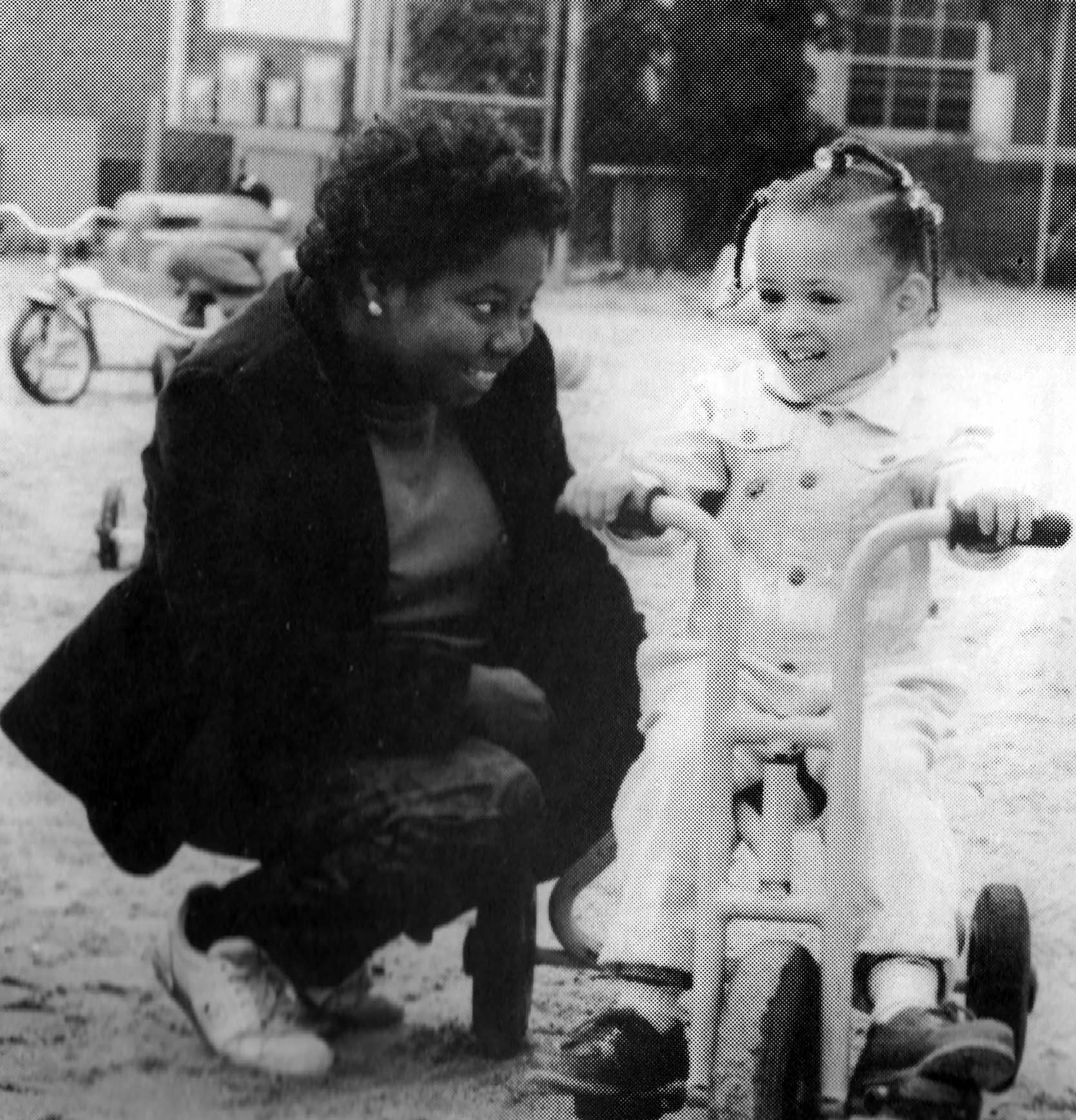

Working for Worthy Wages tells the story of a unique period of activism in early childhood education from the 1970s through 2002. Although there had been activist movements in the field previous to this one, the movement that spanned these three decades was unique in that it was initiated and led by educators who were passionate about their everyday work with young children, yet recognized the need for better pay and working conditions in order to sustain their livelihoods and better meet the needs of children and families. These early educators were often in opposition to professional leaders and advocates in the field of early childhood education (ECE).

The original version of this historical record was published in 2002, when the compensation movement was undergoing a major transition. In response to requests, this update was created by Marcy Whitebook, the original author, along with colleagues Peggy Haack and Rosemarie Vardell. All three women are among the teachers who founded and played leadership roles in the compensation movement from its early phases in the 1970s through the Worthy Wage Campaign of the 1990s.

It is important to note that the authors of this paper are White women and the early movement was largely led by White women. This reflects White privilege and segregation by roles and settings.1CSCCE is committed to eliminating oppressive language and using bias-free terms. Under this philosophy, for example, all terms used to describe race are capitalized, and gender neutral terms are used when appropriate.

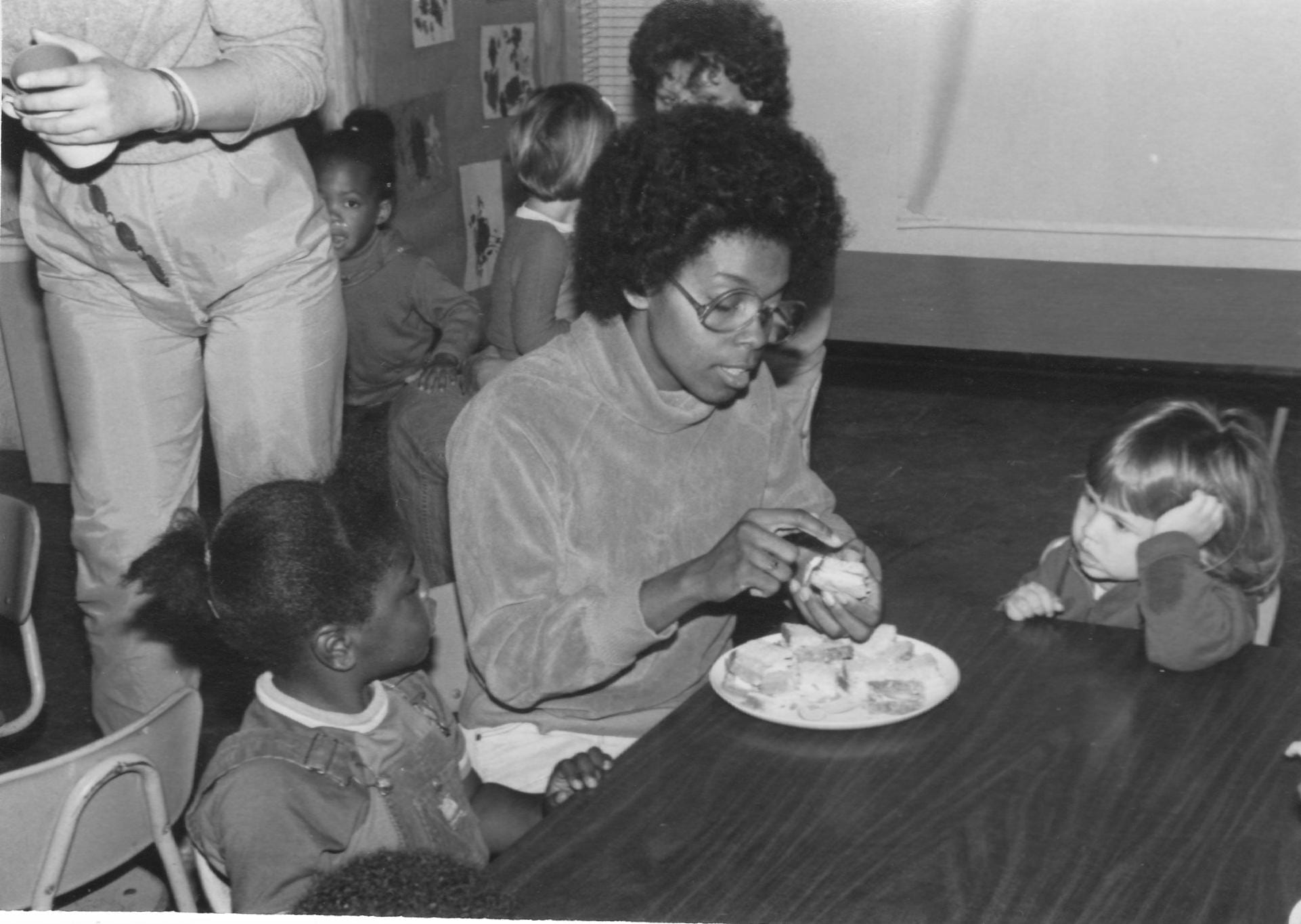

Educators of color were over-represented in family child care and in lower-paying teacher assistant jobs in centers, largely as a consequence of systemic disparities that limited access of Black women and other women of color to better paying jobs. As family child care providers, many women of color found more job opportunities to serve children in their own communities, as well as greater autonomy and job satisfaction. However, these providers were not fully embraced by the compensation movement until the 1990s. As the movement gained momentum and racism was called out, dismantling White supremacy within the movement itself (including by diversifying the leadership) became an important focus.

The authors of this paper have remained involved in different roles in ECE over the ensuing two decades since 2002 and feel the importance of putting this research in its proper historical context. This endeavor includes acknowledging our own biases in the original paper, which quoted and relied heavily on White participants in the movement. We also developed this update as a learning tool for the teacher activists who will write the next chapters of ECE history.

While the original content remains largely unchanged to reflect the authors’ lived history, the format has been improved for readability, and many footnotes have been integrated into the content as they provide relevant information. In addition, at times new information has been included, such as links to information on the ECHOES website, if they help to further contextualize or provide reference to our lived history.

The Early Childhood History, Organizing, Ethos, and Strategy Project, ECHOES, launched in 2023, builds on the story told in this paper and includes a wealth of primary and secondary source materials. ECHOES tells the many histories of the ECE system, undoing the harmful distinctions between child care and early education that almost all ECE histories have reinforced. While the focus of most histories is most often on the perspectives of White women in formal leadership roles and White men with access to power and influence, ECHOES spotlights the untold stories of the women who did the actual teaching of and caring for young children. ECHOES explores the voices and visions of women of color, immigrant women, and working-class women who have made significant contributions but have been left out of most ECE histories. Their experiences, contributions, and activism demand our attention and are centered in ECHOES.

Marcy Whitebook, Peggy Haack, Rosemarie Vardell, 2023

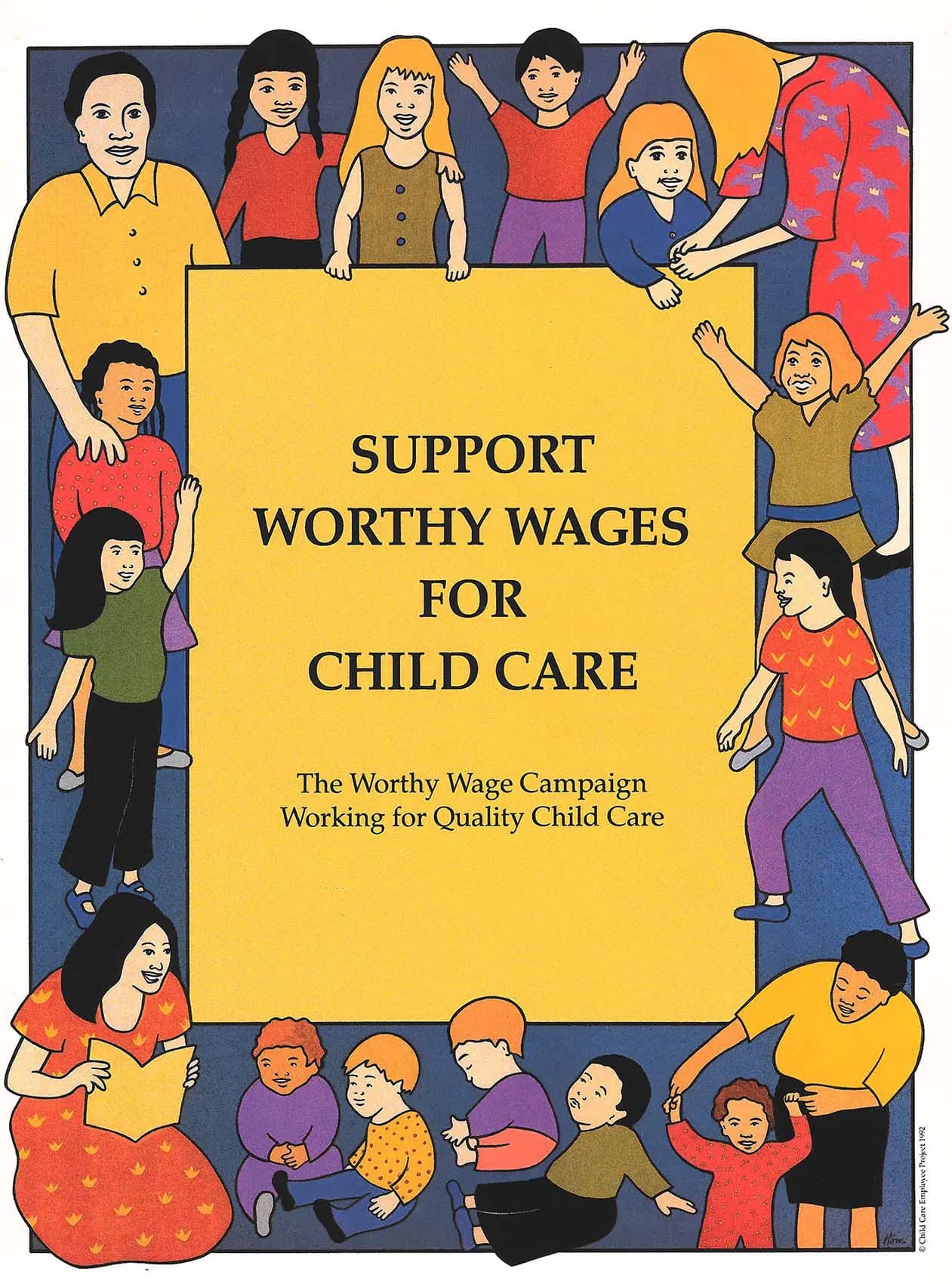

Like other social change movements, the child care compensation movement began gradually in the 1970s with small groups of educators in different states and communities slowly and deliberately expanding their networks, finding one another, and unifying around common goals. This paper focuses primarily on the goal of improving wages, but other goals were equally important: recognizing and respecting the value of the work and those doing the work; and identifying immediate steps to improve working conditions. As the movement matured, the goal of identifying and disrupting racism emerged as a priority, as well. The call for “Rights, Raises, and Respect” endured throughout the movement and efforts to create better jobs began with the creation of model union contracts and model personnel policies, which in the late 1990s evolved into the still-relevant Model Work Standards of today.

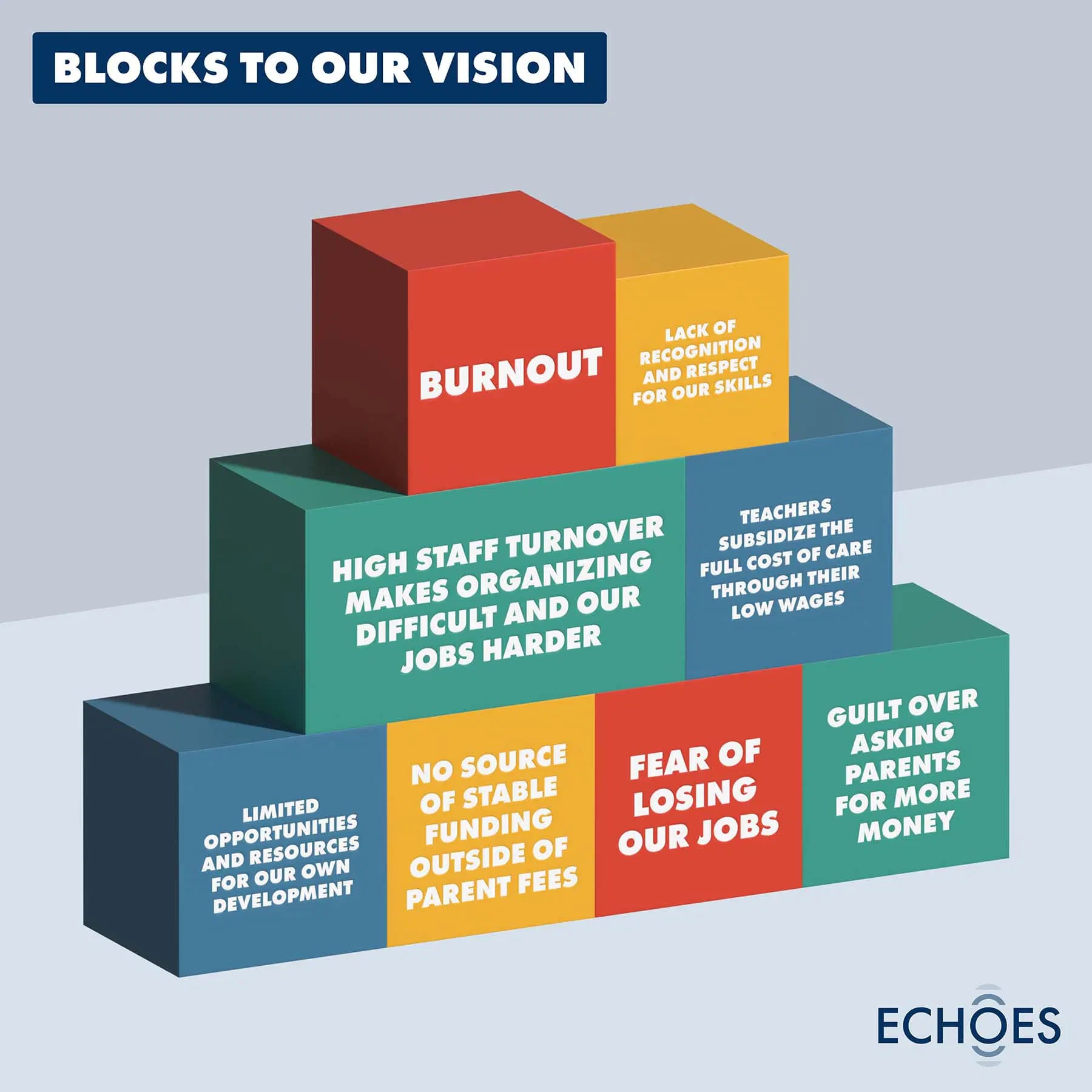

The transition of these efforts to the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) in 2002 marked the end of an era. The ending, as described in this paper, was largely due to the challenge of funding the Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW) as a de facto “organizational home” and the dramatic influx of many new players in the ECE field, which diminished the role of teachers and providers as leaders of the movement. At this same time, a new national concept was taking hold in the ECE field: quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS). While teachers of the movement had come to learn that it was the entire system of early care and education that needed to be fixed, QRIS focused on fixing programs and the people in them. Teachers could not foresee how drastically this approach would impact their lives and change their jobs. The epilogue that follows offers an outline of the continued efforts for worthy wages, a history that is yet to be written.

Today, better compensation for early educators is solidly part of the public discourse and widely recognized as a problem demanding a solution—a legacy in no small measure due to these decades of teacher and provider activism and the strategies of the compensation movement. By learning the history of those who came before, today’s early educators can reclaim their integral role of shaping a transformed vision of the work of teaching and caring for young children and building collective agency to achieve it.

To learn more, delve into the archives of ECHOES, an online project created by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE).

Original Author’s Note

The achievement of worthy wages for child care2While recognizing that terminology is a subject of considerable debate among those involved in and concerned about services for young children, I use “child care” in this paper as a generic term to encompass the many types of early childhood programs that vary with respect to their focus on education and caregiving and the ages of children served. Where appropriate, I distinguish among program types such as Head Start and pre-kindergarten programs. For more discussion of terminology, see Helburn and Bergmann (2002) and the Center for Early Childhood Leadership (2001). teachers and providers3In this paper, I use the term “teacher” when referring to those who work in center- or school-based settings and “provider” for those working in home-based programs, also known as “family child care.” has been the organizing principle of my work life for nearly 30 years. After graduating from college in 1970, I took a job as a child care assistant in a nonprofit parent cooperative, and for the next 10 years, I worked as a teacher of infants, preschoolers, and school-age children in a variety of child care programs. During the 1970s, I also began working with other teachers to improve the wages, working conditions, and status of child care workers, eventually co-founding the Child Care Employee Project (CCEP), which ultimately became the Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW). Throughout the 1980s up to the present, I have been on the “front lines” of research, public education, policy development, organizing, and advocacy efforts focused on the child care workforce.

The paper you are about to read therefore reflects the perspective of a deeply immersed player in the child care compensation movement. This involvement is both an asset and a liability. Not being a historian by training, I have consulted with many other colleagues in order to balance the limits of my memory and point of view. Specifically, I convened dialogues with other “insiders” around the issues of public awareness and education, union and community organizing, and public policy initiatives—all strategies that had been employed during this time period to improve child care jobs. I also conducted in-depth interviews with a number of individuals who were involved in the child care compensation movement or related movements. And as reviewers of earlier drafts have noted, there are even more stories to be told and important questions and themes that deserve greater exploration than I could accommodate here—for example, a comparative study of movements by nurses, public school teachers, and home healthcare workers for improved pay and status.

I acknowledge that there are many teachers, providers, and other activists with whom I was unable to consult due to time limitations. They would add much to this discussion, and without them, there would be no movement at all. While I have tried to be accurate in recounting the movement’s highlights, I may have unintentionally overlooked or misconstrued important events or positions. I hope that readers will forgive any oversights and will understand that my assessment of the movement, while critical at times, stems from a deep sense of honor and gratitude for getting to spend my working life as a part of it. My primary intention has been to reflect upon our past efforts with an eye to informing the work that remains to be done—ensuring that child care teachers and providers receive the compensation, support, and respect that they, and the children and families in their care, deserve.

Marcy Whitebook, 2002

Introduction 2023

Working for Worthy Wages focuses on three distinct phases of the history of the child care compensation movement. During the first phase, between 1970 and 1985, signs of a movement surfaced as the problem of poverty-level wages was identified and publicly articulated, primarily by child care teachers of young children. In the next phase, between 1985 and 1995, researchers demonstrated the link between low wages and quality of services. Community and labor organizing, public awareness campaigns, and public policy initiatives chipped away at the wall of silence around the issue. Finally, between 1995 and 2001, the movement achieved greater visibility through sustained grassroots organizing efforts and creative public policy responses, driven largely by a growing child care staffing crisis, an overall economic boom in the United States, and the passage of national welfare reform legislation in 1996. This phase was also invigorated and inspired by other burgeoning economic justice movements. While not yet drawn into the mainstream of U.S. public policy debates, the issue of inadequate compensation became a staple of discourse and activity within the child care field.

Each of these three phases of the movement are explored with respect to:

- The economic and policy setting at the time, including the level of demand for services, public resources dedicated to child care, characteristics of the workforce, and larger social trends in employment;

- Key players, including their relations to others within the child care community, their links to other movements, and organizational structures and alliances;

- The primary assumptions and key strategies employed by activists, including short- and long-term goals and their organizing, policy, and public education approaches; and

- Accomplishments, missteps, and challenges.

These reflections have been synthesized from group dialogues and individual interviews with other knowledgeable activists and advocates, many of whom are quoted throughout the paper.4Marcy Whitebook conducted dialogues through conference calls that lasted approximately 1.5 hours and included four to seven participants. The topics for the calls were organizing, public policy, and public awareness efforts. Other interviews were conducted over the phone or in person. Unless otherwise credited, all citations in this paper derive from these personal communications which took place between 1999 and 2002. Although people who provided information or perspective were listed in the 2002 version of this report, here we include their names along with their focus group conversations in the Addendum. Other sources include historical materials such as newsletters, pamphlets, and articles. A concerted effort has been made to show how each phase of the movement influenced the next, and how the various challenges facing the movement were resolved or have persisted.

Organizational Name Changes

The “organizational home” for the compensation movement from the 1970s until 2002 underwent numerous name changes, reflecting the movement’s difficult search for a vocabulary and an identity, as well as the debate within the overall field about nomenclature. The changes in the name are described here in chronological order:

East Bay Workers in Child Care (EBWCC)

The original name of the small, community-based group in Berkeley, California, in the mid-1970s.

Child Care Staff Education Project (CCSEP)

A name change in the late 1970s as the word “worker” was not universally embraced and reach was beginning to go beyond the East Bay.

Child Care Employee Project (CCEP)

A name chosen when the group formally incorporated in 1980; this name denoted that the organization was primarily focused on employment issues (specifically wages and working conditions) of those working directly with young children, and it endured throughout the formative years of the national movement until 1994.

National Center for the Early Childhood Workforce (NCECW)

This name was chosen when operations moved from California to Washington, D.C., in 1994. It reflects growth in the movement and the organization’s aim to be inclusive of family child care providers, Head Start teachers, and early childhood teachers in public schools, as well as teachers working in child care centers.

Center for the Child Care Workforce (CCW)

This name change in 1997 simplified the name and avoided any confusion that the organization was addressing issues of child labor; this name continued beyond the transition to the American Federation of Teachers in 2002.

Naming the Problem: 1970-1985

Working for Worthy Wages tells the story of a unique period of activism in early childhood education from the 1970s through 2002. This first part describes the birth of the compensation movement. The key players at this time were center-based child care teachers who experienced and were influenced by the contemporary movements for civil rights, women’s rights, and workers’ rights. They were motivated by a belief that what they did mattered and that their actions could create change not only in their jobs, but in the quality of their work and the funding of the child care system. It all began with naming the problem.

The Setting

The National Landscape

When President Richard Nixon (1969-1974) vetoed the 1971 Comprehensive Child Care and Development Act, child care advocates took up a defensive stance that has persisted to the present day. While President Nixon’s claim that such a program would “Sovietize” American children sounds strangely archaic in the post-Cold War era, at the time it resonated with many citizens who believed that young children should be cared for at home by their mothers. Advocates would wait nearly 20 years for federal child care legislation to pass, and what passed in 1990—the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG, also known as the Child Development Fund)—was far less ambitious than the earlier plan.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, discussion about child care was overwhelmingly disapproving. Child development researchers themselves were conflicted about the effects of out-of-home care on children, particularly for middle-class children. Echoes of this argument continued throughout the time periods addressed in this paper (Belsky & Steinberg, 1978; Belsky, 1984; National Institute for Child Health and Development, 2001).

Ellen Galinsky, a noted child care researcher with the Families and Work Institute, recalled the predominant tone used when describing child care in those days:

When I first became involved in the issue, in the late Sixties and the Seventies, child care was seen as universally negative. That is, I always had the feeling that people thought that children were cordoned behind barbed-wire fences looking out at the world because their evil mothers had left them to have other people raise them. In the research, the typical phrase was “day-care-reared children.”

Status of the Child Care Workforce

During the 1970s and early 1980s, mothers of young children, along with women at all stages of life, entered the paid labor force in unprecedented numbers only to face a grossly inadequate supply of child care services. The child care workforce expanded rapidly during these years, particularly in the center-based sector, and then as now, the workforce was predominantly female. Nearly three quarters of center-based workers were White, in contrast to 2001, when women of color comprised nearly one half of this sector of the industry (Whitebook et al., 2001; Krajec et al., 2001). Center-based workers, on average, were slightly better educated in the 1970s than they were in 2001 (Ruopp et al., 1979).

Home-based providers during this period were found to be exclusively female, but diverse with respect to licensing status, level of education and training, and number of children in their care. Limited data are available about the race of home-based providers in the 1970s and 1980s. 5A 1994 study based on only three metropolitan areas (Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas; Charlotte, North Carolina; and San Fernando/Los Angeles, California) reported that women of color constituted 29 percent of regulated family child care providers, 41 percent of non-regulated family child care providers, and 72 percent of “relative care,” which is described today as family, friend, and neighbor care (Galinsky et al., 1994a.) Their educational levels were generally lower than those of center-based employees, due to lack of access and financial resources for education (Keyserling, 1972; Divine-Hawkins, 1981; Galinsky et al., 1994b).

In its landmark 1972 report, Windows on Day Care, the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) spoke to the inadequate supply and quality of child care services (Keyserling, 1972). The report found that large numbers of children in care were neglected; still larger numbers received care that, at best, could be called merely custodial and, at worst, deplorable. Only a relatively small proportion of children were benefiting from truly developmental-quality care.

The plight of child care workers was central to the NCJW report’s analysis. Among other recommendations, the NCJW called for the investment of federal dollars in child care services, expanding training opportunities, the elimination of “substandard wage scales and excessively long hours of day care personnel,” and the establishment of “professional salaries commensurate with those in elementary education” (Keyserling, 1972). Anticipating criticism of such recommendations, the report argued:

Those interested in children must face the reality that good care is expensive, because good care requires people of ability and training who must be paid adequately if they are to be attracted to this field of work. The quality of day care depends on what we are willing to pay those who are responsible for it. We are shortchanging children when pay scales such as those reported by survey participants were found characteristic of so large a proportion of centers, both nonprofit and proprietary.

Clearly, when wage scales such as those reported occur so widely and on so large a scale, we are asking thousands of nonprofessional workers to subsidize the care of children of other women. We are also excluding from the day care field many women of intelligence and competence who cannot afford to accept salaries as low as some of those described, no matter how rewarding [it] is [to] work with youngsters in human terms. (Keyserling, 1972)

The NCJW report did not directly address whether wage increases should be related to specific levels of education and training, whether professional preparation should be similar to that of elementary school teachers, or whether increases should extend to all who work in “day care” settings, including both “nonprofessional workers” and those who are called “women of competence and intelligence” (Keyserling, 1972). Debate on these issues continued well beyond this time period.

Then as now, concerns about the inadequate salaries of child care workers competed with concerns about the cost of child care services for parents. The National Day Care Study conducted by Abt Associates noted:

While the great majority of these staff earn more than the minimum wage, day care classroom staff are paid far less than the average annual salary of public school teachers. Even those staff whose salaries are at the upper end of the average salary range are earning barely enough to support a family. (Ruopp et al., 1979)

Gwen Morgan, a nationally recognized child care expert at Wheelock College in Boston, Massachusetts, recounted her experiences as an advisor to the Abt Associates study:

Their first draft report suggested that there might be savings in larger group size and slightly lower ratios and that the savings could be used to reduce the price. Two of us in the advisory group objected because if there were savings through the staffing pattern, surely the savings should go to paying more to the staff. To his credit, Dick Ruopp [the study’s director] responded to those comments, and the study did analyze the interrelationship between three factors: ratios, price, and salaries. It was their chart, showing how these factors affect each other, that led to a much better understanding of the systems issue, which later we began to call the “trilemma.”

The child care “trilemma” to which Morgan refers is the interrelationship among salaries, affordability, and supply, particularly in subsidized care. If salaries remained low, the Abt Associates study found, then more children could be served with the same amount of public dollars.

From the very earliest discussion of child care wages, the issue was overshadowed by other financial concerns that were considered more compelling by policymakers and even by advocates.

A Movement Among Movements

In many ways, the child care compensation movement emerged within the larger movement for affordable, high-quality child care, which itself was weakened and directionless for most of the 1970s and early 1980s. The veto of the Comprehensive Child Care Act in 1971 dispersed the broad-based coalition of groups that had worked for its passage, and no new solutions to the issues of affordability and quality readily replaced the vision of a comprehensive national program. Meanwhile, the debate about the role of women and the most appropriate environment for young children raged on.

Though prominent in the day, by and large, neither the labor movement nor the women’s movement actively pursued child care policy and organizing strategies during this period. Union organizing focused solely on workers in publicly contracted programs in Massachusetts, California, and New York. Elsewhere, there was minimal union interest in organizing the child care workforce, particularly in small programs that did not receive public dollars. According to Barbara Reisman, the former Executive Director of the Child Care Action Campaign and a trade union activist in the 1970s:

Women were just becoming more active and more accepted in leadership roles in the trade union movement. And child care [as a job benefit for union members with young children] was certainly brought up as a bargaining issue, but then it was one of those things that easily slid off the table in favor of straight wage increases.

The organized women’s movement was deeply ambivalent about taking a leading role around child care. In some ways, feminist activists wanted to get as far away from traditional women’s work as they possibly could (Maclean, 1999).

Demands for universal 24-hour child care notwithstanding, there was no focus on the working women who were actually providing care or on the issues of child care quality and children’s developmental needs. Child care problems also tended to highlight class distinctions among women, which at that time were not often openly discussed. Reisman commented on the problematic role of the women’s movement in moving these issues forward on a broader scale:

I’m not a historian of the feminist movement, so this is a personal view, but I think that the women’s movement, in its rebirth in the late 1960s, always put child care on the agenda—but it wasn’t up very high. That was partly because, to the extent that the women’s movement took up child care as an issue, there was a sense that it was reinforcing women’s traditional roles, so it was better to talk about other issues. At the same time, at the Child Care Action Campaign, one of the things that the leadership always said was, “Child care is not just a women’s issue.” So we worked hard to get more men involved. But in many ways, [the women’s movement] traded away the potential power of the people who are most passionate about the issue, which is mothers [parents].

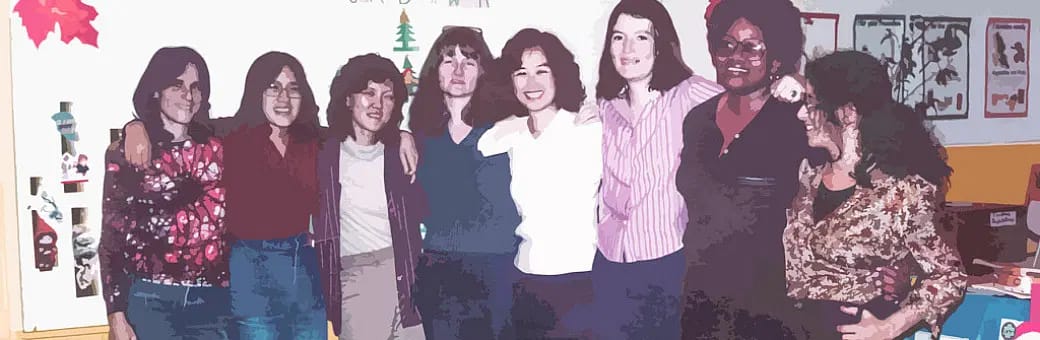

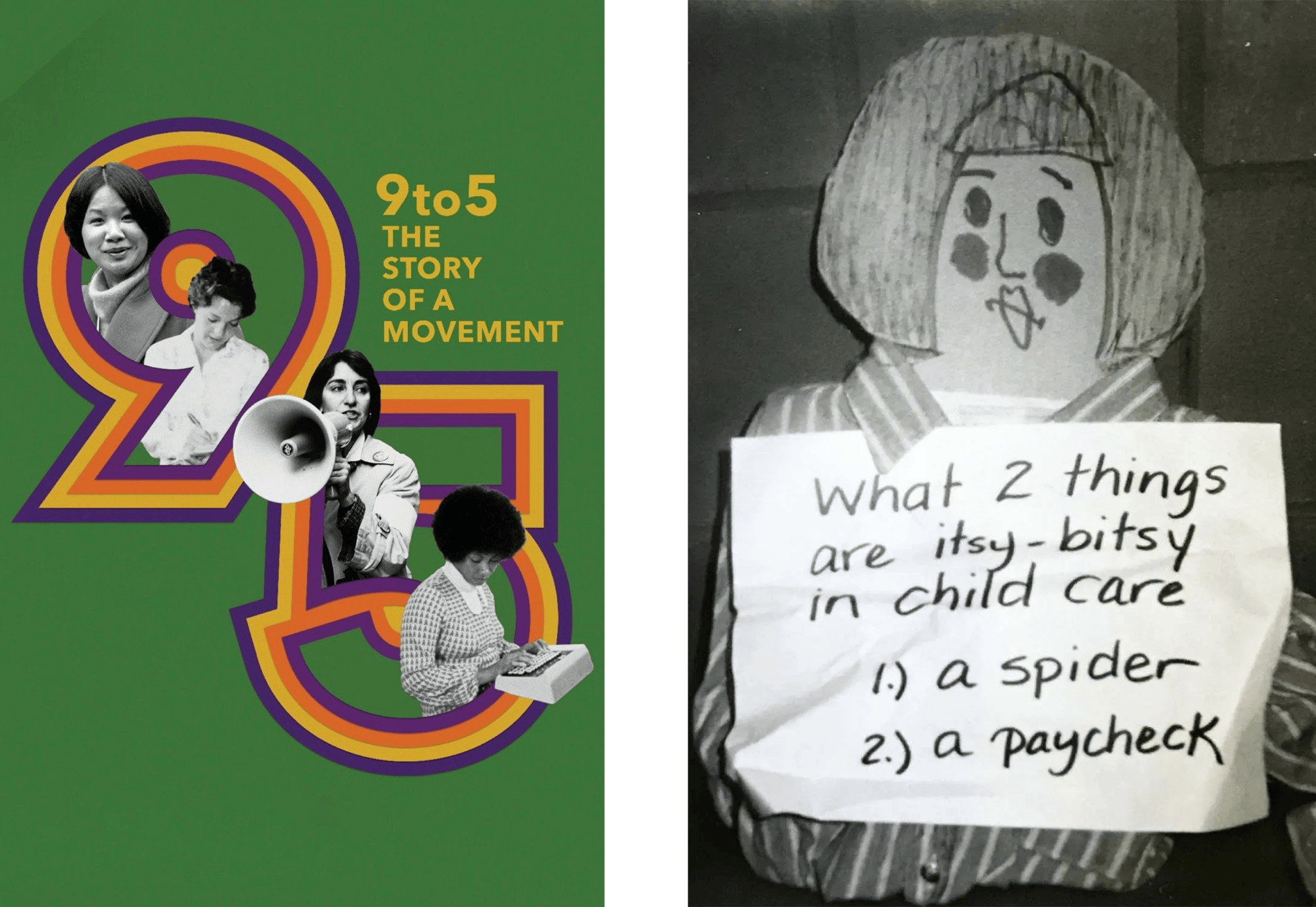

The movement to organize clerical workers in the 1970s intersected both the labor movement and the women’s movement and serves as a useful comparison to the child care compensation movement. As noted in the documentary, 9to5: The Story of a Movement, secretaries also felt invisible in the women’s movement (Bognar & Reichert, 2021). Like child care workers, their demands for better wages and working conditions were further fueled by their insistence on respect for their work, despite it being traditional women’s work. The secretaries put it this way, “We are referred to as ‘girls’ until we retire without pensions.” Similarly, child care workers decried the moniker of “babysitter,” as they called for “rights, raises, and respect.”

Traditional ECE Leaders Fail to Take a Stand on Compensation

Advocates focused on the needs of young children also ignored the compensation problem. Their energies were drawn into the massive transformations occurring within the ECE field during this period. In addition to an influx of teachers and providers resulting from the increasing demand for services, many new positions emerged for directors, trainers, resource and referral agency staff, owners of for-profit centers, and entrepreneurs of companies supplying materials to child care programs. Also at this time, for-profit child care business owners, whose success rested in large part on low wages for teaching staff, became organized into their own associations, creating new debates within the field about regulations, training, personnel management, and other business practices.

In particular, the child care workforce sought support from the prominent professional association in their field: the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC).6Founded in 1926 as the National Association of Nursery Education (NANE), the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) nearly tripled its membership between 1975 and 1995. By 2001, more than 100,000 members were organized into more than 450 affiliate groups throughout the country. For a discussion of the organization’s history, see Hewes, 1996; NAEYC, 2001; and Urban Institute, 2001. Their efforts, however, went unrewarded. While the ranks of NAEYC swelled several-fold during this period, NAEYC leadership was composed primarily of academics and other highly educated, predominantly White professionals, only some of whom had direct experience working with children on a daily basis. Among those leaders, many had little familiarity with full-day child care, as the organization itself had its roots in the nursery school and part-day program tradition.

Profession or Occupation?

“Professionalism” became a watchword in the field. While the National Council of Jewish Women had distinguished between “nonprofessional aides” and “professional teachers” in its 1972 report, the notion that anyone working in child care was or could become a “professional” held tremendous sway by the end of the decade, particularly within NAEYC. Child care advocates and leaders within NAEYC, however, often used the term “professionalism” to specifically exclude discussion of one’s economic needs as a worker, claiming that such a focus would “deflect our energies away from the quality of life we provide for children” (Katz, 1994). Demands for better pay were subsequently set in opposition to professional behavior, despite the fact that sociologists identified increasing the economic well-being of its members among the benchmarks for the development of an “occupation” into a “profession” (Goode, 1960; Larson, 1997).

Adding to the tension among those promoting early childhood education as a profession was the use of the term “worker” by some child care teacher groups. These teacher activists believed that change would only occur through organizing. Despite the fact that most of these teachers were well educated, they believed that education and training had to be inextricably linked to better wages. Leaders in the field, on the other hand, promoted the idea that achieving better education and training would automatically lead to higher pay. This idea persists despite its failure to ensure salaries commensurate with education.

Key Players

Against this backdrop, small groups of child care teachers in a number of communities across the country—Ann Arbor, Michigan; Berkeley and San Francisco, California; Boston, Massachusetts; Madison, Wisconsin; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and New Haven, Connecticut—began to talk about child care wages and working conditions. While these groups emerged separately from one another, their members shared many characteristics. Predominantly White, young, and college educated (often in the field of early childhood education), they were veterans of the women’s, civil rights, and anti-war movements of the late 1960s. They were also predominantly female, although a significant number of men working in centers were also drawn to these groups—well out of proportion to their overall numbers in the child care workforce.

Most of these teachers described their work with young children in political terms, as being central to women’s liberation, racial equality, and economic equity. As a result, they found deeply disturbing the contrast between their idealistic view of the high potential of child care work and the low value placed on it not only by society, but by ECE leaders, the women’s movement, and labor unions. Given the orientation of the times, it was an easy step to view improving child care jobs as a political cause.

Coauthor Peggy Haack, a child care teacher, later family child care provider, in Madison, Wisconsin, was active in MACWU, the Madison Area Child Care Workers United. Nancy deProsse was a Boston-area teacher activist and a founding member of BADWU (Boston Area Day Care Workers United), the precursor of a statewide union movement in Massachusetts. Both women voiced similar perspectives during our conversations about the early phases of the movement:

Haack: My first child care experience was a very, very oppressive work environment that put me on the path to activism as soon as I got out of college. I thought, “Oh my God, what is happening here?” I got involved with several people who formed a support group and met for Sunday brunch. We were bonded by the fact that we knew that what was happening in child care was wrong. We were largely White and well educated. We were really idealistic, and we considered our child care work as political activity because we had been engaged in other social change movements and realized how those experiences had transformed us. We were all poor, but there was a strong sense of purpose and self-satisfaction in working for a cause we believed in so strongly. I think that is the interesting thing: I look back, and it was a really good time in my life. We were going to change the world! The people who were gathered together were all from small nonprofits, all taking care of poor children, engaged with families, and really wanting to make a change in society. We realized early on that we had to support each other because life was unfair. So at the same time that we were trying to change things, we were initially quite a cohesive group that enjoyed being together and working together.

deProsse: I have always thought my education at Wheelock College [a private teacher education college in Boston, Massachusetts from 1888 to 2018] was somewhat responsible for my decision to organize. They did everything they could to convince me not to go into child care. They thought that it was not a professional field. I had received that good education from them and had been taught about quality early care and education programming. So, when I got to my first day care center, I realized that the actual situation going on was nothing like they said early care and education should be.

Teachers in these groups were aware of the challenges facing the larger child care movement, as deProsse explained:

The other thing that was going on was that people still were thinking women should be working at home, and so child care was totally not accepted as an industry that should even exist. Women were organizing around just being able to demand more child care. There really was not a provider movement or an advocacy movement or anything at that point. There were just women demanding child care, and child care workers trying to figure out what they were going to do to make it better. That was the scene in Massachusetts…. During this period, people didn’t want anyone to say anything bad about child care, because they thought it would keep society from supporting it. So, if we admitted that quality wasn’t good or that pay was inadequate, it would just be fuel for those who thought that women should stay at home.

In addition to their commitments to economic justice and racial equality, these teacher activists were, by and large, steeped in child development practice and theory and proud of that knowledge base. They believed their professionalism was melded with sensitivity to issues of economic justice, racial equality, and cultural diversity and felt stung by an emerging feminist critique of efforts to professionalize caregiving, which were believed to undermine low-income communities and cultures (Joffee, 1977). It often appeared as if feminist leaders only called upon child care workers when it came to caring for their own children or to provide child care during women’s movement meetings and events.

Collaborations and Conflicts

During this period, collaborations began to develop between members of these fledgling child care worker groups and organized labor. There were numerous attempts to unionize, with varying degrees of success. While they did not necessarily agree on how to conduct a union campaign, these activists shared a central commitment to improving the wages and status of child care workers.

Simultaneously, many of these teacher activists experienced highly strained relationships within the ECE field, facing resistance both from co-workers and leaders as they sought to make compensation an issue. Joan Lombardi, who began her career as a Head Start teacher and then a center director, shared the following reflection when she was Director of the Child Care Bureau, under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, during the administration of President Bill Clinton (1993-2001):

In 1978 or ‘79, compensation was not an issue. People didn’t talk about it. It was a time where people really felt like they should just do this work for “the love of kids,” and that was it. Most of the work in the beginning was just documenting that [low pay] was a problem.

The notion that women worked for “pin money,” 7“Pin money” means a small amount of money used for nonessentials. The term originally referred to the budget a husband would allocate his wife for clothing and other personal expenses. The phrase was used to belittle women’s wages.rather than to support themselves and their families, was only beginning to be displaced. Discomfort with talking about financial matters, coupled with a dominant ethos in the field that one worked with children out of love rather than financial need, squelched open discussion about poor compensation. Politics, age, and style also came into play. The child care teacher advocates were progressive activists, comfortable with challenging the status quo. Typically, they were a decade or two younger than much of the ECE leadership, and generational tensions of the time spilled over into these relationships. These teachers saw the leadership (or “Establishment”) as stodgy, conservative, and out of date. The leadership saw them as unladylike, unprofessional, and self-involved. On more than one occasion, various teacher activists were pulled aside by leaders and mentors in the field and urged to “let the compensation issue go” and to focus instead on the real issues of classroom practice and the needs of children. To those who came of age in the “personal is political” era, this “guidance” seemed insulting and downright wrong.

Teachers Leading the Way

The organizational structures first adopted by various teacher groups around the country resembled consciousness-raising or support groups. Typically, they were small collectives that operated on consensus decision making. They created support networks, developed local newsletters, and did outreach in their communities.

The Berkeley group, which would ultimately evolve as the “organizational home” of the compensation movement, was an outgrowth of a class offered by a community adult school run by local progressive activists. It first called itself East Bay Workers in Child Care, offering drop-in support sessions for child care teachers and developing handouts addressing specific problems such as breaks, inadequate materials, unpaid overtime, and lack of input into decision making at their centers.

The Boston Area Day Care Workers United (BADWU) was the first teacher group to affiliate with a union. In the mid 1970s, BADWU affiliated with the largely healthcare-oriented Union 1199 but found that, at least in that area of the country, the union was not prepared to deal with small child care workplaces. They next affiliated with District 65, United Auto Workers (UAW), which had a progressive and democratic tradition as well as extensive experience in organizing both small and large workplaces. The Madison Area Child Care Workers United (MACWU), which modeled its name after the Boston group, followed in their footsteps in the early 1980s after a failed effort to unionize with a small independent union of restaurant workers. Although not pursuing unionization, groups in Ann Arbor, Minneapolis, and elsewhere shared the collective structure. While initially formed by teachers, some expanded to include home-based providers, directors, and others who were committed to improving child care compensation.

In many ways, these early activists saw themselves as isolated warriors, because the other constituencies from which they had emerged or with whom they identified—the women’s movement, the early education field, and/or the labor movement—had little interest in dealing with the economic needs of child care workers. This isolation made their connections with one another all the more important.

In 1979, at the annual NAEYC conference in Atlanta, members of the Berkeley group made a presentation about working conditions and status, which they described in the Child Care Employee News as “raising more eyebrows than support” (Child Care Employee Project [CCEP], 1982c). At the 1980 NAEYC conference in San Francisco, activists from throughout California, as well as Madison, Ann Arbor, Boston, and Minneapolis, found each other and agreed to plan a session on employee issues for the following year in Detroit. Those who were present at the 1981 session recalled the irony and symbolism of having more people on the panel than in the audience for this daylong event.

The following year, at the association’s conference in Washington, D.C., these same groups formed the Child Care Employee Caucus within NAEYC. Later known as the Worthy Wage Caucus (hereafter, the Caucus), this coalition articulated specific demands to make NAEYC more responsive to the needs of those who work directly with young children. With a primary focus on issues of professional development, NAEYC was highly resistant to most of the Caucus’s demands at the time. Despite the largely negative response, NAEYC had the benefit of solidifying the Caucus as an opposition force and further fortifying the growing ties among its members.

Over the next two decades, the Caucus would serve as a vehicle for sharing information and raising awareness (some might say, a ruckus) within the larger professional community. In 1981, the California-based Child Care Employee Project (CCEP), formerly called East Bay Workers in Child Care, received funding from the Rosenberg Foundation to produce a national newsletter for the movement, and the following year, CCEP agreed to take on the coordination of the Caucus. During this initial phase, there was a high level of agreement among the member groups, even though they were pursuing somewhat different strategies, as discussed below. They all shared a loosely defined expectation that NAEYC would eventually carry the mantle of child care workers’ needs, as had occurred for public school teachers within such organizations as the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers. But enlisting official NAEYC support for the cause proved to be a much more formidable challenge than activists anticipated.

Initial Demands of the Child Care Employee Caucus to NAEYC Leadership

These were the very first demands made by the newly formed Caucus in 1983:

- Establish a regular column in the NAEYC journal Young Children dealing with working conditions;

- Earmark some NAEYC membership action grants for projects that support worker concerns;*

- Increase NAEYC members’ involvement in selecting conference topics;

- Increase employee-related conference sessions;*

- Create a sliding fee scale for conference registration based on salary; and

- Arrange accommodations at the conference that child care workers can afford.

Throughout the 1980s until the mid-1990s, when NAEYC Leadership eliminated it, Caucus members used the Membership Expression of Opinion before the NAEYC Governing Board at the annual conference as the main vehicle for publicizing its concerns. Along with other progressive activists within the organization who were focused on issues of anti-bias education, gay and lesbian rights, and anti-violence issues, Caucus members staged creative and elaborate displays and demonstrations. This “guerrilla theater” served to draw many new supporters to the various causes and also greatly increased the rancor between the activists and the NAEYC leadership. Those who had come to child care through their progressive politics saw nothing wrong with this mode of protest, whereas many in the organization were surprised or put off by it.

*These were the only two demands that were met to some extent. Read more in “NAEYC: Nap Time Over?” (CCEP, 1982-1983).

Primary Assumptions and Key Strategies

Reflecting the influences of their previous political activities, teachers in activist groups understood that improving the wages, working conditions, and status of child care workers would require a variety of strategies. Traditional workplace organizing was viewed as an important tool for improving child care jobs, but it was also necessary to pursue a public policy strategy to leverage additional public resources beyond parent fees in order to create the necessary funding base for change. From the onset, this movement was about more than improving the lot of child care workers: they directly connected the well-being of children and families with their own well-being. Teacher advocates were explicit about the link between the quality of child care jobs and the quality of services. They wanted more respect and better pay for themselves, but they were just as deeply committed to upgrading the care and education of young children and to making child care affordable and accessible for all families. The earliest materials of the Child Care Employee Project carried the following statement, which was echoed in the writings of other groups:

CCEP believes that the quality of care children receive is directly linked to the working conditions of their caregivers. Low pay, unpaid overtime, lack of benefits, and little input into decision making create tension in programs and lead to high staff turnover. The exit of trained staff from the field gnaws away at the morale of those who remain and limits efforts to build consistent, responsive environments for children. (CCEP, 1982a)

While these groups shared a high level of agreement about the nature and consequences of the problems, various groups emphasized different strategies. For example, early on, CCEP focused on documenting the problem, while BADWU committed its energy to organizing and state policy work. But along with its union drive and its coalition work on state policy with other social service and trade union groups, BADWU also worked on a statewide salary and benefits survey in coordination with the Boston-area resource and referral agency. Likewise, CCEP worked closely with District 65 members who were seeking to organize for-profit child care centers in Northern California, while they operated a child care worker support group, engaged in local political campaigns, and developed many training and educational materials for teachers and providers.

All of the groups attacked the problem from several directions, recognizing that no single strategy would work by itself and learning from each other’s successes and failures. While they shared a belief in public support for an expanded, high-quality system for the education and care of young children, there were few specific demands or campaigns addressing financing and public resources at this point in time. Throughout this period, there were debates within and among the groups, but conflicts over strategy seldom surfaced very openly, perhaps because the ongoing conflicts with groups outside of the Caucus served to limit internal dissension.

The most active groups of the period—working in Madison, Boston, Minneapolis, Berkeley, and Ann Arbor—all articulated ambitious agendas for themselves. Serving as an example of these groups, the Boston group BADWU articulated a three-pronged mission, as recalled by Nancy deProsse: 1) to organize workplaces; 2) to bring people together around discussions of how to improve quality of care in our centers; and 3) to bring people together around political action. Written materials from BADWU in this period identified the following specific goals:

- To acknowledge that child care is worthwhile work;

- To give workers input into their working conditions and the quality of care through a union contract;

- To make child care work a career that people can consider staying in by increasing pay and benefits, developing stable and secure funding sources, and offering free in-service training;

- To develop the attitude that child care is an economically essential program in this country and strengthen parental options for their children’s care; and

- To educate child care workers about the politics of day care and include them in policy formulation, advocacy, and lobbying (CCEP, 1982b).

CCEP recognized the importance of highlighting the problems faced by child care workers and enlisted the support of those who could help them conduct a credible study. Bob Fitzgerald of the National Jury Project helped train teacher volunteers in the San Francisco Bay Area to collect data. Emily Werner of UC Davis assisted in data analysis. Staff at BANANAS Resource and Referral (Oakland) and the San Francisco Children’s Council provided support in the development and execution of a survey. The entire study budget of $200 was raised through events and donations, part of which went to help one of the teachers buy an appropriate outfit for visiting centers!

The CCEP study led to the article, “Who’s Minding the Child Care Workers? A Look at Staff Burn-out” (Whitebook et al., 1981), published in Children Today and based on a study in which 95 San Francisco child care teachers were surveyed. The study identified low pay as the major source of staff burn-out and turnover. Circulated among teachers and advocates throughout the country, this article laid out the following blueprint for change, including research, policy work, organizing, and training:

To meet the needs of child care staff for a decent income and of parents for affordable services, either government or industry will have to bear its share of the cost. Obtaining increased financial support will require changing the prevailing view that child care is unskilled work and enhancing public appreciation of it. As long as child care work is considered unskilled, this will be reflected in its pay and status.

Thus, already-overworked child care staff members must join together to inform the public about their work’s value and the level of skill required. This involves informing legislators and policymakers of work conditions and defining the minimum employment standards that need to be included in future legislation and guides for establishing centers. It requires pressuring organizations that represent child care workers, like the National Association for the Education of Young Children, to focus more of their resources on working conditions. Finally, organizations might be created to help workers share ideas about break and substitute policies, contracts, and health insurance and to offer workers support.

Amelioration of the situation that leads to burn-out requires changes within centers and in the broader community. Tackling burn-out by reassessing a center’s existing organization can be time-consuming and initially awkward. But such a process can also have the effect of energizing staff and improving work relations by helping workers see that they are not personally responsible for their unsatisfactory working conditions. It can be a valuable beginning in addressing the larger tasks that face the field: publicizing and legitimizing child care work and allocating to it the social and financial resources it needs and deserves. (Whitebook et al., 1981)

This strategy blueprint from 1981 retains relevance in 2023, as the work of caring for young children remains undervalued and our politicians and industry leaders fail to allocate the social and financial resources the work needs and deserves. The skills required to do the work, however, are now more clearly articulated, and more training and education is required. In 1981, the assertion that child care was skilled work was contradicted by the fact that very little was required in the way of pre- or in-service training for those who worked with young children in child care settings. In part, this assertion may have reflected the feminist perspective held by teacher activists that emphasized the hidden competencies involved in traditional women’s work. It may also have reflected the composition of the teacher activist groups that were largely women with high levels of formal education and specialized early childhood training.

Accomplishments, Missteps, and Challenges

Despite the often-negative reception to their message, teacher activist groups accomplished an important shift within the ECE field.

Visibility

Simply put, child care teachers became visible in ways they rarely had before. Gwen Morgan emphasized that there was considerable discussion at the time about child care quality and looking at the “whole picture”:

What changed, I think, was that […] you didn’t just go away. You kept coming back with the facts and the figures and the organizing. So, I think that gave people a much broader sense that there’s no way you can solve child care problems at the expense of the people who work in child care.

It became more and more difficult to ignore the organized groups of teachers at conferences and meetings, particularly in combination with reports that documented their low pay and inadequate benefits. While many of the issues raised had already been articulated by the National Council of Jewish Women in the early 1970s, there was something more compelling in the fact that teachers themselves were now raising them. These groups made the profession as a whole take notice of child care workers, whether they wanted to or not. Although their words and efforts did not quickly move the field as a whole to action, their messages resonated with many center staff, family child care providers, researchers, trainers, and other practitioners, many of whom would join the movement over the next decade.

Through their various activities, these groups were also developing much-needed language for discussing how staff working conditions influenced children’s learning environments and the extent to which wages should be emphasized over other workplace issues. The initial writings and discussions among these groups jump-started a process of defining the new movement’s most pressing issues.

The early studies conducted by CCEP, the Minnesota Child Care Workers’ Alliance, University of Michigan in Ann Arbor researcher Kathy Modigliani (1986), and others also broke important ground in the arena of “action research.” Using their extensive knowledge of the child care world, they developed and piloted surveys of teachers and providers that remain the basis of much of the workforce research done today. Recognizing the limits of their own fledgling research skills, child care teachers enlisted the help of more established academics and activists and were able to produce credible breakthrough reports.

Perhaps most importantly, teacher activists were becoming increasingly aware of how these data could be used not only to advance, but also to hinder the cause. CCEP, in particular, began to develop information and share resources to help other teacher activists “make salary statistics work for, not against you” (CCEP, 1986).

Exploring Social Change Strategies

The other major contribution of these groups during this period was to explore the applicability of popular social change strategies—most notably, comparable worth and unionization—to the plight of child care teachers. Doing so revealed the particular challenges facing the child care workforce. In the early 1980s, comparable worth provided the theoretical basis for much of the organizing around pay equity and affirmative action for women in other industries, including clerical workers and others employed in hospitals and on college campuses (Maclean, 1999). But early on, child care activists realized that the structure of most of their industry—small jobs that typically did not employ other classifications of male workers—made comparable worth more useful as a public awareness strategy than as a specific method to remedy discrimination, which could not legally be proven in most child care settings (Whitebook & Ginsburg, 1985).

The active communities had widely varying experiences related to union organizing, shaped largely by different circumstances in their states with respect to prior organizing and the structure of public funding of child care for low-income families. As a result, a great deal of discussion in the early days of the movement focused on the applicability of unionization to the child care workforce. In California, for example, many of the publicly funded centers housed in the public schools had been unionized shortly after World War II, and many Head Start programs in Southern California were unionized in the 1960s. Due to cuts in the state budget, later attempts in the 1970s to unionize community-based, state-subsidized nonprofits in San Francisco were unsuccessful. In addition, many of the teachers who were active in CCEP were working in small independent nonprofits that were unable to attract the unions’ attention. In contrast, a wide network of state-contracted centers in Massachusetts lent itself more readily to the successful organizing drive begun by BADWU and District 65 in the late 1970s. Madison activists had only moderate success with unionizing city-funded centers serving low-income families on vouchers. Without some significant source of public funding or other source of funds, there was little to bargain over that didn’t lead to higher costs for parents.

As progressive activists, these teachers were generally pro-union in principle, whether they were engaged in a union-organizing drive or not. They understood that workers in other occupations had traditionally improved their jobs through collective-bargaining strategies and saw the need for an organization to protect and represent child care workers on the job as well as in the larger political arena.

They also saw that a union contract could ensure manageable teacher:child ratios, adequate break and classroom preparation time, and greater staff input into decision making, which would lead to improved care for children. Nancy deProsse recalled:

When we started the idea of a union in the Seventies, we did not think about anything else as a possible solution. We needed to have a worker’s say in what was going on in child care, and that seemed to be the only way to go at it. So that is what started it here. We really believed unionization was going to be what worked for us because it had worked for other professions.

A 1983 article in the Child Care Employee News delineated the many positive reasons to unionize as one response to the run-of-the mill anti-unionism that was so prevalent at the time and frequently used by opponents to discredit Child Care Employee Caucus members, CCEP, and the movement as a whole. The article also outlined the following barriers to union organizing in child care:

- Small shops in child care deliver little in dues revenue to unions;

- Workers organizing in small workplaces are easily identified and vulnerable;

- Unions are resistant to organizing such a fragmented workforce, particularly given high levels of staff turnover; and

- Unions can be resistant to adapting their traditional strategies to the specific needs of child care worksites, particularly the close personal relationships between clients and workers and sometimes between management [directors] and staff (CCEP, 1983).

Teachers voiced concern about becoming lost within a larger organization, where many fellow union members might have stereotyped or negative views of child care and child care workers. In California, this concern was largely traceable to the experience of school-based child care center teachers, who had joined a public school teachers’ union. Many felt they had become second-class citizens within the union. Some teacher activists also feared that by unionizing, they might become isolated from or “lost to” the larger compensation movement. According to Peggy Haack, some Madison teachers found it difficult to maintain a satisfying relationship with a union:

In Wisconsin, we were at a disadvantage because we did not have contracted centers. Wisconsin always had a voucher system, and so we did not have the leverage that others did to go after the big programs and organize them. Other types of child care programs didn’t necessarily fit with the union. As much as it seemed like the right path, we did not know how to do it, people were not prepared to do it, it took so much time to accomplish, and it was not a very compassionate model. Key leadership roles in the fledgling union movement were held by men, and in a female-dominated field, that put off some people.

Developing Teacher Voices

The concept of “teacher voice” stood out as a unique feature of the child care movement from its inception. The on-the-job experiences of teachers were the cornerstone of the movement, and they were reflected in the framing of the issues and strategies, as well as in the development of resource materials. The groups that were not actively involved in union organizing at this point—such as CCEP, the Minneapolis Child Care Workers Alliance, some of the MACWU teachers, and the Ann Arbor group—nonetheless developed strategies to support community organizing and to build teacher skills as advocates and leaders. This emphasis on teacher voices reflected a synthesis of the consciousness-raising strategies many had learned in the women’s movement and the ECE field’s emphasis on the importance of making each individual feel nurtured and respected.

A Movement Lacking Resources

Accomplishments notwithstanding, the movement suffered from certain weaknesses. First and foremost, it was hampered by woefully inadequate financial resources with which to build a strong organization. Because it was outside the mainstream of early childhood groups, there was limited support available from charitable organizations. With the exception of the San Francisco-based Rosenberg Foundation, an early supporter of CCEP, philanthropic funding was scarce. And because the child care compensation issue had not yet been embraced by a larger progressive community, foundation dollars would not be forthcoming for several more years. Union resources provided some support for child care activism in Boston, Madison, and Northern California, but it was always tight.

Child care compensation was a “bake sale” movement, although the goods most commonly sold were buttons, bumper stickers, and t-shirts with such slogans as “Give a Child Care Worker a Break” and “Rights, Raises, Respect.” Individual donations and memberships provided some support, but given the limited resources of the core constituency, there was resistance to charging more than a nominal fee, if any, for most services.8NAEYC dues at the time were about $30 per year. Although relatively low for a professional organization membership, this amount was beyond the reach of many who worked with children. In contrast, CCEP initially charged $5 per year for its newsletter but would always make it available for free. This accessible fee, however, did not cover most of CCEP’s expenses.

The issue of resources was not only a challenge on the organizational level: the early leaders of the movement also understood the need for a large investment of public funds in child care to adequately address the needs of parents, children, and ECE workers. But with the defeat of national child care legislation, a tight economy, and a growing critique of federal investment in human services, there was a reluctance to make a call for universal public funding the centerpiece of its strategy. A later “devolution” of federal funding to the states meant that local and statewide solutions would become ever more important, but as yet, there were no models for creative policy initiatives. As Joan Lombardi noted, “In the Eighties, there was still a sense [at the policy level] of not knowing what to do about wages.”

By this time, publicly funded pre-kindergarten programs had been established in several states, and the movement was aware from salary studies that these programs paid higher salaries. However, public pre-kindergarten programs were not viewed as a viable strategy in the early years. Many of these programs operated only half day, and most movement activists were focused on expanding full-day child care services for working parents.

The Shifting Composition of Activist Groups

The composition of the early activist groups was also problematic in terms of building a movement that would represent the child care workforce as a whole. Most of the early teacher-leaders were White, under 35, and college educated at a time when women of color and workers with fewer years of education were increasingly entering the field. As the movement matured and diversified, there was a gap between the demographics of the founding leaders and many of their constituents. Furthermore, the roots of the movement lay in the center-based sector of the child care industry. None of the early groups anticipated the tremendous shift toward family child care in the coming decade. They would have to struggle to rethink their relationship to family child care providers, whom they often saw as business people rather than fellow child care practitioners with many common concerns.

There was also the problem of teacher-leaders in these groups moving out of the classroom and away from teaching to become center directors, resource and referral agency staff, or teacher educators or to assume other nonclassroom roles, often in order to support themselves and their families more adequately. Many of the early allies of the movement were also drawn from those who had left the classroom. Thus, while the groups represented child care teachers, they were not necessarily teacher-led. CCEP addressed this problem initially by ensuring that at least 50 percent of its board members would be teachers or providers and, frequently, by hiring part-time staff who also worked part time in the classroom. This issue of being representative of the workforce would call out for resolution as the movement grew.

Professionalism: An Internal Conflict

As addressed previously, the movement also experienced internal conflict around the issue of professionalism. On the one hand, many teacher activists resisted the focus on increasing training and education without addressing the economic realities of child care work. They firmly rejected the notion that increased levels of education would automatically deliver better pay and respect. Many teachers who had a background in the labor movement and the left felt uncomfortable with language around professionalism that they considered elitist.

On the other hand, many of these same teachers were well trained in child development. They considered themselves “professionals” and believed strongly that people working with young children should receive child-related training. While the early movement often emphasized the need for accessible, affordable training and for keeping child care affordable for parents, activists were often unable to counter the perception that they were interested only in wages to the exclusion of all other “professional” concerns.

Underestimating the Opposition

The early movement was fueled by its members’ firm belief in the righteousness of their cause, as well as their experiences from the 1960s that led them to believe they had the power to transform society. To this generation of activists who had witnessed the anti-war, civil rights, and women’s movements, exposing oppression and organizing around it were seen as the most important steps toward change. This worldview allowed these teachers to take on the formidable task of restructuring how society perceived the care of young children. It also meant that these activist teachers underestimated their opposition, spread themselves too thin, and did not think strategically enough about organizing a power base—in part, because of their emphasis on individual transformation and consciousness-raising. While they recognized the limitations of existing organizations such as labor unions and NAEYC, they did not pay enough attention to building their own organization, even as it became increasingly clear that not all child care workers would be able or willing to unionize and that NAEYC was unlikely to reinvent itself as a teacher and provider organization. The latter was particularly true given NAEYC’s growth in membership from other sectors of the field, including profit-making operations whose success rested largely on the low wages of teachers.

CCEP became the de facto national group after securing some limited funding to coordinate local efforts around the country. However, CCEP’s membership revenue was minimal, and it never figured out how to offer services (such as health insurance) that would attract a substantially larger membership base. CCEP was also continuing its local education and organizing work in Northern California. A continual reliance on philanthropic support would prove to be a very shaky foundation on which to build the lead organization in the movement.

As this first phase of the child care compensation movement drew to a close, it faced significant internal and external challenges:

- How to build its ranks to reflect the changing child care workforce;

- How to develop a power base and an organization led by teachers and providers, given the limits of existing unions and professional organizations;

- How to legitimize the voices and needs of child care workers and how to build better alliances, within and beyond the established child care community;

- How to articulate goals that simultaneously embraced the commitment to education and training and to higher wages;

- How to design winnable policy reforms, given the diverse and under-resourced structure of the industry; and

- How to develop strategies that would draw public attention to the problems of child care workers.

Worthy Wages as the Key to Better Child Care: 1985-1995

This second phase of the child care compensation movement began addressing the questions and challenges that emerged from the work of the first era: building individual and organizational power; creating alliances outside the child care community; articulating clear and specific goals; designing winnable policy solutions; and continuing to draw attention to the problems of child care workers.

But tremendous changes occurred during the decade spanning the late 1980s and early 1990s. Fueled by the ongoing influx of mothers with young children into the labor force, expansion in the industry gave rise to new institutions, strengthened previously ignored or weak sectors, and diversified the number and types of players in the field. Resource and referral agencies proliferated, supported by corporate as well as state dollars. For-profit child care chains mushroomed and joined with conservatives to exert pressure on policymakers to limit standards, expand vouchers as the vehicle for subsidizing low-income families, and allow for-profit programs to access public subsidies.

The Setting

Major Changes in Child Care

Child care advocates and other stakeholders once again began to organize around federal child care policy, building a broad coalition around the Act for Better Child Care (ABC), which ultimately became the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG)(Cohen, 2001).

Attention also focused on family child care as never before. Activists and service agency staff began to understand the large proportion of child care that this sector provided, and they grappled with how to offer training and other support services that meshed with the particular needs of home-based providers. As Arlyce Currie of BANANAS Child Care Resource and Referral based in Oakland, California, observed:

Family child care—at least in this state—was, for the most part, underground. Very few people were licensed, let alone doing that kind of care in any recognized way. In order to get the supply up, because of the burgeoning need at that point, a lot of us in resource and referral and in the teaching institutions started focusing on family child care.

Many child care supporters latched on to family child care as the best way to build the supply of services, particularly for children under the age of three. For some, the pull toward home-based care was economic, since it was seen as a cheaper vehicle than contracted centers for serving low-income families. Meanwhile, the ECE field was adjusting to the notion that the child care workforce included both center- and home-based providers and that public dollars would also be distributed to unlicensed care under the mantle of “parental choice.”

During this decade, awareness about child care infused society as never before. As Nancy deProsse noted, “Child care was more accepted by the Eighties than it had been in the early Seventies,” which opened up new possibilities in policy and organizing. While policy discussion still focused primarily on the needs of low-income families, the renewed and broader interest in child care reflected its emergence as a middle-class phenomenon. Families across the economic spectrum were struggling to meet their child care needs, and employers of relatively affluent white-collar workers were beginning to feel more pressure around this and other work and family issues. Driving the expanded demand for child care were the loss of earning power in real wages for most American workers, soaring divorce rates, and the rising feminization of poverty, all of which increased the number of dual-parent and single-parent working families.

Public Policy Creates Challenges

Public policy moved in two contradictory directions during this period: on one hand, the lowest-paid sectors of the workforce expanded, making it harder to improve child care salaries, and on the other, new initiatives were developed that implied potential improvements for many, yet resulted in concrete gains for relatively few. The rapid expansion of the voucher system meant that contracted programs, which traditionally had negotiated better reimbursement rates and paid higher salaries, faced major new competition: for-profit and home-based care was often cheaper and tended to offer substantially lower worker earnings. Vouchers also led to market rate studies that, in an under-resourced market, placed the better-paying programs and providers at a disadvantage. Nancy deProsse recalled the scene in Massachusetts:

There was less accountability as the market rates were put into place, but it has also really impacted the unionized workers’ ability to get wage increases and better benefits. Once you have a market rate, reimbursements are keyed to a certain level of those rates, and those at the top end [such as unionized centers] can’t increase their levels.

Shannah Kurland of Direct Action for Rights and Equality (DARE), a Rhode Island group that helped family child care providers organize for better pay and benefits, added:

The whole concept of using a market rate in an industry that is so artificially deflated just keeps rates low. It is a stupid policy for those of us trying to improve jobs, although it is smart for the state because it keeps costs down. But for a lot of our providers, [the voucher system] has actually been driving up their pay because they are at the very bottom tier of a low market. So it is a short-term gain, but it is not a long-term solution.

Helen Blank of the Children’s Defense Fund and Joan Lombardi recalled a similar phenomenon:

Blank: [With the advent of vouchers], now you couldn’t craft a salary strategy that affected the whole child care system. Vouchers were a major setback in terms of being able to tackle compensation.

Lombardi: I think that was the big policy shift that affected whether we would move forward with adequate salaries. If we had gotten the Comprehensive Child Development Act in 1971, it would have funded programs. We would have had a set number of programs, infusing them with program standards, including staffing requirements. Although vouchers have given parents some flexibility—especially those who work on the weekends and at night, and that’s very important—on the salary side, they have become part of the challenge.

Public Policy Creates Opportunities

During this same period, the two largest federally supported ECE systems demonstrated that public dollars could be used to dramatically improve salaries and reward professional development for child care teachers and providers. The 1990 Head Start Expansion and Quality Improvement Act (later renewed) led to the allocation of some $470 million in salary increases for approximately 100,000 Head Start personnel: an average per-employee increase of about $1,500 per year from 1991 through 1994. In military child care, the Caregiver Personnel Pay Plan was launched in 1989 to create an ongoing system-wide program linking training with increased compensation. As Helen Blank observed:

With the Head Start reauthorization [in 1990], we were able to put in the quality and salary set-aside provisions, and you had members of Congress on both sides avidly supporting it. That was another turning point, because the issue of wages in this field was now recognized in federal law.

Joan Lombardi was employed then as the liaison in Washington, D.C., for the Child Care Employee Project, and along with others, she advocated successfully to include improved compensation as a legitimate “quality enhancement activity” for states and communities to pursue with CCDBG funds. The availability of this federal funding stimulated a variety of creative experiments and models for improving compensation at the state level across all sectors of the ECE industry and led to new professional development opportunities for many center-based teachers and home-based providers (Montilla et al., 2001).